Inflection Journal Vol.09

Collaborators: Aurelia (Tasha) Handoko, Yutong (Kelly) Jin, Bridget McNab, Ioanna Petropoulou

Published: December 2022

Editorial: Healing scars / Make do and mend

Repair is a loaded word. On the surface it is seemingly benevolent and optimistic. Indeed, to repair is to acknowledge that something broken requires fixing. However, its application is subjective. To some, repairing suggests a return to halcyon days of a former time, a retroactive process of “making [something] great again.” To others, repair is anti-utopian, a rejection of tabula rasa principles, a challenge to accept the damage of our time and create something new with the broken pieces.

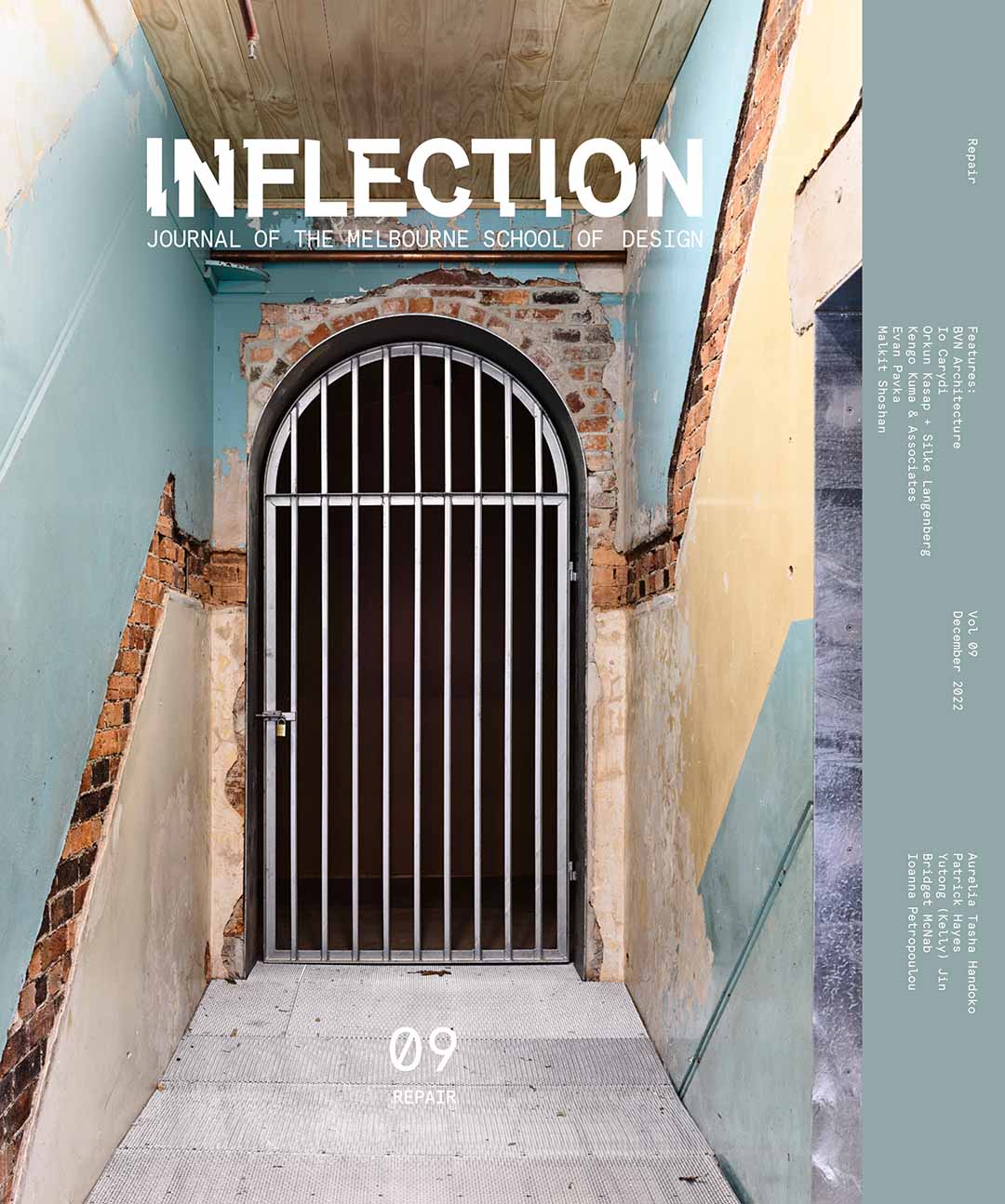

The Abbotsford convent, this volume’s cover image, is no less charged. Founded by The Sisters of the Good Shepherd in 1863 and repurposed as an artist retreat at the forefront of Melbourne’s creative scene, the precinct grapples with traumatic history as the former site of a women’s asylum and Magdalen laundry – a site characterised by abandonment, exploitation and brutality. In light of this, Kerstin Thompson Architects’ renovation of the convent’s Sacred Heart Building makes a poignant statement by embracing its old, stripped and flaking walls. This approach reveals important questions: How do we heal our environment while acknowledging the scars of the past? And, to what extent should we repair?

In her article, Notes on the Architecture of UN Peacekeeping Missions, Malkit Shoshan investigates UN peacekeeping bases as an infrastructure of societal repair on similarly contentious ground: post-conflict Mali. While on the surface the UN’s infrastructure of repair appears benevolent, Shoshan reveals that the material presence of temporary restorative interventions and actions remain indefinitely, often to the detriment of the surrounding natural environment and existing culture. Here, healing scars creates new wounds.

Repairing damage equally has implications of concealed history. In Australia, repairing colonial infrastructure masks the fact that 200 years of European built heritage has been to the detriment of the country’s Indigenous cultural landscapes. Beneath the University of Melbourne’s colonial heritage grounds, natural creek systems carrying short-finned eels once valued by local Wurundjeri people are now invisible to the eye, rerouted into subterranean storm drains. [1] The layers and complexity of history may be extinguished in choosing to restore historic buildings. As such, we ask how we can repair without erasing, simplifying, or hiding the complexity of the past.

Rejuvenating former industrial areas into natural landscapes and deluxe developments, a common theme of many adaptive reuse projects, hides an uncomfortable truth: the built industry has historically exacted significant environmental harm. Indeed, this volume’s theme was originally inspired by the repair of other violent ‘scars’ on the landscape: the Latrobe Valley’s open-cut mines in Victoria, one of the world’s largest known brown coal deposits. Aligned with COP26’s goal of limiting coal mining and fossil fuel usage, the Victorian Government is in the process of retiring the Latrobe Valley’s mines. Ironically, the Rehabilitation Strategy by Engie and Arup proposes flooding the pits to create a series of artificial lakes, erasing the industrial scars only to make a pseudo-return to nature while exacerbating the environmental damage to the region.[2] Reflecting on the words of landscape designer Gilles Clement, as curators and stewards of the “global garden” that is Earth, we asked our contributors to question how architects and practitioners can repair anthropocenic environmental damage without inducing further harm.

In his article, Rhizomatic Rejuvenation, Andrew MacKinnon imagines a long-term design strategy for the Latrobe Valley in stark opposition to the current official solution. His work sings the complexities of repair. The adapted thesis proposes five humble architectural gestures, generated over long periods of time, that individually reflect the deeply complex histories and stories of the site. Industrial influence is rife in the use of existing structures and materials; consultation with the First Nations people, the Gunaikurnai people is advocated for in each development stage with shared governance of the site; and phytoremediation is a priority and exists in the architectural program as well as an ongoing maintenance. Here, the repair is more than architecture, it acknowledges that buildings are part of systems: social, global, ecological and economical. Their existence either supports or questions the ever-consuming and ever-growing state of the world. When do we stop buying and building anew and look to repair what exists?

The 2021 Pritzker Prize winners, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philip Vassal ask the same question through their work.[3] When designing, their first task is to stop and think, and to decide whether to intervene. The simplicity of this question unravels our current fixation on the capitalist notion of continuous newness and an ignorance towards what is and was. In this issue, Evan Pavka’s piece celebrates this dichotomy through an exploration of rubble. Record of Rubble investigates the stories that contemporary ruins present; the historical memories of what exists and how these begin to dictate their own places. Focusing on Detroit, the industrial rubble is unpacked as political, social and economic mirrors of the city. Here, history is ubiquitous and acknowledged to the detail it deserves, directly speaking to the richness of the repair process.

Similarly, in Kengo Kuma’s Shipyard1862, the architects eschew the glamour of renovation to instead adopt a bare bones and sombre approach to their intervention. Hiding contemporary technology such as new HVAC and acoustic systems inside existing rusting pipes, the building presents an honest materiality that allows visitors to thoughtfully connect with the building’s past, its former inhabitants and its legacy.

The current trend of material overconsumption and waste necessitates repair through recycled and renewable sources. We act as though resources are endless, yet material abundance is an illusion. According to a recent study updating the 1972 The Limits to Growth research, if the world maintains its current economic and population growth rates, the complete absence of natural materials will be seen within 20 years.[4] In response, BVN Architects’ Quay Quarter Tower serves as an optimistic precedent, revolutionising material reuse on a grand scale. Inheriting a mid--century skyscraper in central Sydney, the architects and developers made the daring decision to forego the wrecking ball and instead, appropriate the existing concrete structure, expanding and recladding the building in a contemporary skin. The form and appearance of the existing building is hardly recognisable; the new tower cantilevers and curves where the old was boxy and banal yet, BVN’s project illustrates that opportunities to reuse and repair lie beyond skin deep. The new building may be a glamorous reincarnation but in retaining the existing concrete structure it has profoundly reduced its material carbon footprint. The project proves that architecture can move into its next state of being by adapting rather than eliminating the existing.

Faced with the wicked crises of our world, from historic injustices and global inequalities to the rapidly warming climate, repair may seem a naive and Sisyphean task. However, as all of the pieces in this issue describe, to repair is a chance to reflect, to hone in on and recalibrate our vision for our built and natural environment. This volume does not hide the fact that repairing is a tedious, sometimes unsuccessful and counteractive process. Nevertheless, Joan Tronto’s words serve as an optimistic comfort, as she advocates for architects to “care.” We suggest that repairing is a method of caring, a chance to think critically about our profession, practices and methods.

While repair is an acknowledgement of a broken system, it is also a means of salvaging and embracing what is important.

Notes:

[1] Zach Hope, “One eel of a story: the slippery truth of a fishy underground migration,” Age, February 6, 2021.

[2] Miki Perkins, “Latrobe Valley mine 'pit lakes' risk river health in drying climate: reports”, Sydney Morning Herald, December 10, 2020.

[3] Samanata Kumar, “Anne Lacaton and Jean-Phillipe Vassal - Winners of 2021 Pritzker Prize.” Rethinking the Future, published August 7, 2022, https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-news/a3729-anne-lacaton-and-jean-philippe-vassal-winners-of-2021-pritzker-prize/

[4] Gaya Herrington, “Update to limits to growth: Comparing the World3 model with empirical data,” Journal of Industrial Ecology (Yale University), vol. 25 (3), 614-626.